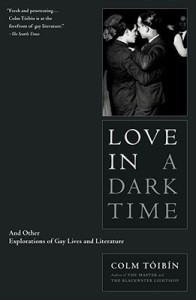

Love in a Dark Time: And Other Explorations of Gay Lives and Literature

Colm Tóibín

Scribner: trade paperback (1st edition: 2004)

261 pages

I’ve recently moved into a new apartment, and one of the first things I do when I move to a new place is get a library card. I have a collection going, seven cards strong. And so, after obtaining my fresh and shiny library card, I did my second favorite thing, which is raid their queer shelf. It wasn’t the biggest selection I’ve ever seen, but I did pick up a few good books I’m excited to delve into, one of which is Hiding in Hip Hop.

Love in a Dark Time is also one of the books I picked up, a collection of relatively short portrait essays by Colm Tóibín about various gay authors and artists. “I realized that certain writing done in the hundred years between the trial of Oscar Wilde and the rescinding of the Victorian laws against homosexuality in Ireland raised fascinating questions,” says Tóibín in his introduction. “Some of the greatest writers of the age were fully alert to their own homosexuality. In their work, they sought to write in code, yet they managed also, once or twice, despite their own reticence and the dangers involved, to tell the truth in their fiction, to reveal the explicit drama of being themselves.” He also calls the collection a “tentative history of progress,” and though I might quibble with whom has benefited from this progress, the collection shows a movement of progress nonetheless.

Overall, I liked the writing of the essays, it was clear, concise and informative. I learned things, and got swept up in the description of a party attended by both Tóibín and Spanish filmmaker, Pedro Almodóvar. But all-in-all at the end I wasn’t left feeling an undeniable urge to seek out more work by these authors or learn more about them, like I was with Eminent Outlaws. Tóibín’s collection was more of a miniature study of something particularly specific in these men’s lives, and less of the literary history and criticism I was expecting. Mostly, what I wanted out of this book was more of everything, more background, more history, more information on these men, their works, and their lives. And though the essays in themselves and individually were good, I would have also liked less of a history lesson, a recitation of facts, and more analysis from Tóibín about the connections between these men and between these men, our community, and literary history.

Because the essays had such a singular focus, my favorites were the ones about authors I already knew, namely the chapters on Wilde, Bishop, Baldwin, and Doty. Though I also liked his last or conclusion chapter “Good-bye to Catholic Ireland” probably because that’s where Tóibín’s voice comes through strongest and at its greatest length instead of in small vague paragraphs. I would recommend this book mainly as a companion to reading the texts of the authors Tóibín discusses–selections from this collection would be interesting to teach with–but I wouldn’t recommend it to a light reader or someone interested in wading into lgbtq or literary history.

Though less interested in tracking down the black diary of Roger Casement, I am now interested in tracking down Tóibín’s old reviews for The London Review of Books that he mentions in his introduction:

Without my realizing, The London Review of Books decided on another method of enticing me to confront my own sexuality in print. They began to send me books about gay writers or by gay writers, and some of these books were too interesting to resist. Thus I found myself writing constantly on the work and lives of homosexual writers.

So that may be my next project, elbow deep into the archives of The London Review of Books to find the reviews that forced Tóibín to confront his own sexuality in print.